▼

> Urban Visions in Star Trek Into Darkness

J. J. Abrams is an american director who decided to develop a story showing the events before the old Star Trek franchise. Into Darkness is the last Star Trek, and part of its plot takes place on earth, where San Francisco and London suffer terrorist attacks. In the 24th century these cities may look like these astonishing images.

"'Our philosophy about doing cities, and respecting the canon of how the work is described by Gene Roddenberry, is that you’re only a few 100 years in the future. You’re not that far away. If you look historically at the way somewhere like London has changed in the last 100 years, there are many buildings that would potentially still exist. We go through this process of, ‘What would have happened? What buildings would they have hung on to? How would it have changed the nature of some of the design choices they made?'"

"We like to take things that are real and try to make the architecture scalable. In other words, a scale that is not just totally ridiculous and massive. At the same time, you want a few landmarks in those shots to get the sense of what city you are in. In that case, there’s St. Paul’s Cathedral and the River Thames. We even went to London and took a lot of pictures from different angles, to try to maintain the real geography of it. But, at the same time, we want to elaborate on that and use our imagination on how that might have changed."

(Star Trek Into Darkness trailer)

(citation taken from here)

> Is There a Limit to How Tall Buildings Can Get?

Concerning the 'Not Tall Enough' posts, I decided to publish here an interesting article written by Nate Berg last year for Atlantic Cities website (link on the left). The competition to get the highest skyscraper is stronger than ever, such as the competition to idealize it, to dream it... Therefore, in technical terms, what is the frontier between utopia and reality?

"The race is always on. Within the span of just two years, the world's tallest building was built three times in New York City – the 282.5-meter Bank of Manhattan in 1930, the 319-meter Chrysler Building in a few months after, and then 11 months later the 381-meter Empire State Building in 1931. The era of architectural horse-racing and ego-boosting has only intensified in the decades since. In 2003, the 509-meter Taipei 101 unseated the 452-meter Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur after a seven-year reign as the world's tallest. In 2010, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai far surpassed Taipei 101, climbing up to 828 meters. Bold builders in China want to go 10 meters higher later this year with a 220-story pre-fab tower that can be constructed in a baffling 90 days. And then, in 2018, the Kingdom Tower in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia will go significantly farther, with a proposed height of at least 1,000 meters.

Will this race ever stop? Not in the foreseeable future, at least. But there has to be some sort of end point, some highest possible height that a building can reach. There will eventually be a world's tallest building that is unbeatably the tallest, because there has to be an upper limit. Right?

Ask a building professional or skyscraper expert and they'll tell you there are many limitations that stop towers from rising ever-higher. Materials, physical human comfort, elevator technology and, most importantly, money all play a role in determining how tall a building can or can't go.

But surely there must be some physical limitations that would prevent a building from going up too high. We couldn't, for example, build a building that reached the moon because, in scientific terms, moon hit building and building go boom. But could there be a building with a penthouse in space, beyond earth's atmosphere? Or a 100-mile tall building? Or even a 1-mile building?

The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, a group interested in and focused on the phenomenon of skyscrapers, recently asked a group of leading skyscraper architects and designers about some of the limitations of tall buildings. They wondered, "What do you think is the single biggest limiting factor that would prevent humanity creating a mile-high tower or higher?" The responses are compiled in this video, and tend to focus on the pragmatic technicalities of dealing with funding and the real estate market or the lack of natural light in wide-based buildings.

"The predominant problem is in the elevator and transportation system," says Adrian Smith, the architect behind the current tallest building in the world and the one that will soon outrank it, the kilometer-tall Kingdom Tower in Jeddah.

But in terms of structural limitations, the ultimate expert is likely William Baker. He's the top structural engineer at Skidmore, Owings and Merrill and he worked with Smith on the Burj Khalifa, designing the system that allowed it to rise so high. That system, known as the buttressed core, is a kind of three-winged spear that allows stability, viably usable space (as in not buried deeply and darkly inside a massively wide building) and limited loss of space for structural elements.

This illustration (above) from SOM shows how the buttressed core of the Burj Khalifa compares to the traditional structure of the Willis Tower. (This image is an adaptation of a graphic that originally appeared in this article on Baker and the buttressed core from the December 2007 issue of Wired.)

Baker says the buttressed core design could be used to build structures even taller than the Burj Khalifa. "We could go twice that or more," he says.

And though he calls skyscraper design "a fairly serious undertaking," he also thinks that it's totally feasible to build much taller than even the Kingdom Tower.

"We could easily do a kilometer. We could easily do a mile," he says. "We could do at least a mile and probably quite a bit more."

The buttressed core would probably have to be modified to go much higher than a mile. But Baker says that other systems could be designed. In fact, he's working on some of them now.

One idea for a new system would be buildings with hollowed bases. Think of the Eiffel Tower, says Tim Johnson. He's chairman at the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat and a partner at the architecture firm NBBJ, and he says any really, really tall building would have to be like a supersized version of the Parisian icon, otherwise the lower floors required to support the gradually narrowing structure would be way too big to even fill up.

For a Middle East-based client he's not allowed to identify, Johnson worked on a project back in the late 2000s designing a building that would have been a mile-and-a-half tall, with 500 stories. Somewhat of a theoretical practice, the design team identified between 8 and 10 inventions that would have had to take place to build a building that tall. Not innovations, Johnson says, but inventions, as in completely new technologies and materials. "One of the client's requirements was to push human ingenuity," he says. Consider them pushed.

With those inventions and the hollow, Eiffel Tower-like base, Johnson says the design could have worked. The project was canned as a result of the crash of the real estate market in the late 2000s (and probably at least a little good old-fashioned pragmatism). But if things were to change, that building could be built, he says. "We proved that it is physically and even programmatically possible to build a building a mile-and-a-half tall. If somebody would have said 'Do it two miles,' we probably could have done that, too," Johnson says. "A lot of it comes down to money. Who’s going to have that kind of capital?"

As far as the structure is concerned, others think it's possible, too. My colleague John Metcalfe recently pointed out a 1990s-era concept for a two-and-a-half-mile volcano-looking supertower in Tokyo called the X-Seed 4000 that has a similar Eiffel Towerishness to it.

As Metcalfe notes, this 4,000-meter "skypenetrator" was never built for a variety of reasons, but the most obvious is that "[r]eal estate in Tokyo isn't exactly cheap. The base of this abnormally swole tower would eat up blocks and blocks if it was to be stable." In fact the base of this structure, according to conceptual drawings, would have spread for miles and miles, almost like the base of Mount Fuji, itself about 225 meters smaller than the X-Seed 4000.

A building taller than a mountain seems preposterous. But according to Baker, it's entirely possible.

"You could conceivably go higher than the highest mountain, as long as you kept spreading a wider and wider base," Baker says.

Theoretically, then, a building could be built at least as tall as 8,849 meters, one meter taller than Mount Everest. The base of that mountain, according to these theoretical calculations, is about 4,100 square kilometers – a huge footprint for a building, even one with a hollow core. But given structural systems like the buttressed core, the base probably wouldn't need to be nearly as large as that of a mountain.

And this theoretical tallest building could probably go even taller than 8,849 meters, Baker says, because buildings are far lighter than solid mountains. The Burj Khalifa, he estimates, is about 15 percent structure and 85 percent air. Based on some quick math, if a building is only 15 percent as heavy as a solid object, it could be 6.6667 times taller and weigh the same as that solid object. A building could, hypothetically, climb to nearly 59,000 meters without outweighing Mount Everest or crushing the very earth below. Right?

"I'd have to come up with a considered opinion on that," says Baker.

How about an unconsidered opinion?

"I'm afraid I'm going to have to chicken out on you and not give you a number," Baker laughs. "This is the kind of thing I'd want to do with a student."

"If you get some funding for a grad student for a semester, I'll give you a number," Baker says.

So we still don't really know what the tallest building ever would be. In the meantime, Everest-plus-one is essentially the highest. But like the ever-moving crown for the tallest building in the world, even this estimate could rise with a little investigation. Any grad students out there got a semester to spare?"

(article originally taken from here)

> 'Not Tall Enough' Series - Ultima Tower

It is not the first time I show an architectural utopia planned by Eugene Tsui. This genius has a lot of projects that blow our mind - like The Eye in the Sky Lookout Tower -, and he is known by applying his comprehensive understanding about the world into the structural plans. To imagine the highest skyscraper is nice, but it is important to think about its utility and feasibility. Eugene Tsui do it very well, maybe to compensate his drawing weaknesses. So, Ultima Tower is a two-miles high skyscraper, proposed in 1991 to be part of San Francisco. Actually it is intended to be a new city, made by different small ecosystems and where one million people could live. Tsui is worried with global overpopulation, therefore, soon or later ideas as Ultima Tower start to be a way to develop real solutions.

Tsui seems to be crazy - Ultima Tower is the second highest proposed building ever -, but the details he put on the plan make it a not so distant possibility. First, the structure is cooled by a system of waterfalls in the lower levels, that make the cool air raising through the building. Photo-voltaic cells and wind turbine energy generators are installed on the tower surface, but the most innovative energy source is the differential in air pressure between the ground floor and the top. "Each of the 120 levels is treated as an entire landscaped neighborhood with a 'sky' 30 to 50 meters high and inbuilt lakes, streams, rivers, hills and ravines give a natural setting to the flatter soil on which residential, public and commercial structures can then be built." The mobility system inside Ultima Tower include a compressed air elevator and a vertical train that services 30 floors at once. Tsui estimated the costs as well. $150 billion is the price to build this wonderland.

"The trumpet bell shape, modeled after the highest structure created by a creature other than human, the termite's nest structures of Africa, is a most efficient form for its compressive characteristics allow the thickness of the upper supporting walls to be uniform in thickness down through the bottom of the building. No other shape can dispel loads from top to bottom, is effectively aerodynamic and retains such stability in a tall building. The size of its base would completely enclose the entire financial district of San Francisco, approximately 7000 feet across, and contains four of the world's largest waterfalls surrounded by garden terraces. Gardens are situated at all exterior and interior openings. The whole tower could be thought of as an upward extension of the earth with layers of vegetation growing, level by level. All residences have a minimum of 100 feet by 100 feet of property where 50% of the property is covered by natural vegetation."

Structure ID

Name: Ultima Tower

Place: San Francisco, California, USA

Height: 3217 meters

Function: Mixed

Author: Eugene Tsui

(Eugene Tsui official website)

> What Are Utopias For?

This is an article originally written by Ljubo Georgiev and Anita Stamatoiu for the Autumn 2011 edition of Edno magazine.

"Some of architecture's greatest ambitions have always been to imagine, to look ahead, to bring change. Often architecture has been charged with the task not only of making the world a better place, but also of transforming mankind. Whether architecture can actually make a difference by giving shape to bold ideas is the main topic of the 2011 edition of Sofia Architecture Week, entitled "Architecture Unlimited?" The event will explore the extent to which architecture can (still) function as a transformative tool for the urban environment in an age in which utopian ideals have been replaced by city marketing, and making improvements to the cityscape is often subordinated to making a profit.

"Some of architecture's greatest ambitions have always been to imagine, to look ahead, to bring change. Often architecture has been charged with the task not only of making the world a better place, but also of transforming mankind. Whether architecture can actually make a difference by giving shape to bold ideas is the main topic of the 2011 edition of Sofia Architecture Week, entitled "Architecture Unlimited?" The event will explore the extent to which architecture can (still) function as a transformative tool for the urban environment in an age in which utopian ideals have been replaced by city marketing, and making improvements to the cityscape is often subordinated to making a profit.

Bold ideas are not only a phenomenon of the present day or the recent past. Even in the most distant ages, visionaries dreamed of perfect worlds of harmonious co-existence. Most often these worlds were expressed in the forms of cities, perfect cities. The following examples show this dimension of (architectural) utopian thought. They demonstrate how highly ambitious architecture has often been in the past in tackling the task of changing the world.

The ideal city as a reflection of human aspirations for idealized life can be found in every major culture across the world. This time it did not all start in Greece… but in China. The Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE) developed a vision of organizing the country according to the sacred geometrical principle of the Magic Square. According to the Chinese, an ideal society could take shape through an ideal division of space: from the private home to the entire universe. A couple of centuries later in The Republic, Plato described a perfect society aimed at constantly educating its citizens in the ideal city of Kallipolis.

These models developed separately, but they both advocated an idealized environment, in which society could harmoniously proliferate. Some people took these ideas quite seriously, however, and many Chinese capitals (Chengzhou, to begin with) or Greek cities (Pireaus) would try to follow these philosophical models. Like many other Greek inventions, the Greek model was adopted by the Romans, who established their cities upon a uniform grid, characterized by the Cardo and Decumanus (image above). This was a universal system for spatial orientation, which had it roots in the desire to control the whole world, but which also implied a distinct social order.

Centuries later, advances in maritime transportation, as well as the invention of printing, offered new means and horizons for communicating visions. This resulted in utopian ideas that were often a mixture of ancient principles, exotic stories and commercial interests. Thomas More, for example, was strongly inspired by ancient stories and was the first to use the term "utopia" in his book Utopia (1516). The title meant "no place," while the book depicted a fictional island in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean where there was no private ownership, with goods being stored in warehouses and people requesting what they needed. There were also no locks on the doors of the houses, which were rotated between the citizens every ten years.

Although More called his book Utopia, he was not the only one to fantasize about possible worlds. The Renaissance brought us detailed descriptions of ideal cities organized according to ancient principles of geometry and astrology, such as Filarete’s City of Sforzinda (image above, 1465). Not only geometry, but society, too, was supposed to be “ideal”. In Tommaso Campanella’s The City of the Sun (1623), goods, women and children were held in common, whereas Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1627) was characterized by generosity and enlightenment, dignity and splendor, piety and public spirit.

The conquerors of South America were looking for such mythical worlds when they set out in their search for the Indies. Having found a land of untamed nature, wealth and fertility, European idealists would soon engage in building a utopian Christianised society far from the burdens of Europe. This impulse towards aggressive implementation of an ideal continued all the way up to the late 20th century with the plan for Brasilia: a newly built Modernist city in the middle of the Amazon jungle.

Such utopian thoughts finally saw a chance at realization with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. In order to fulfill their dreams, people suddenly had not only political will at their disposal, but also the power of the machine. Industry did not provide only opportunities, however. It also brought about the rise of the great industrial cities, crowded with poorly paid and unhealthy workers who lived in terrible conditions. The avant-garde socialist Charles Fourier spoke out for these people, developing the concept of the Phalanstère (image above, 1808): detailed plans for a remote community of around 1,600 people working in cooperation for a mutual purpose. Lack of financing prevented him from seeing his grand-hôtel in the real world, but later in the same century Godin in France and Ruskin in the US set up working colonies that took their inspiration from Fourier’s work.

Fighting social injustice and terrible living conditions was the main driving force behind industrial utopias. King Camp Gillette wrote The Human Drift (1894), a social plan that envisioned Metropolis (image below), a three-level mega-city of millions of people, built on the site of Niagara Falls and getting its power supply from the waters. Ebenezer Howard took refuge in traditional values in his description of The Garden City, a planned settlement built in harmony with nature. Led by such ideas, Unwin and Parker made building the garden cities of Letchworth and Welwyn possible. A contemporary flashback to the garden city utopia is American suburban sprawl: an “ideal” environment of coexistence between man and controlled nature.

Inspired by the power of the machine, some visionaries decided to set the bar even higher. Societies all around the world embarked on a quest: to build the New Man. [The New Man: the ideal individual, which most 20th century ideologies (fascism, nazism, communism) were aiming to create. The New Man would need no gods, he would be a rational, integrated, altruistic and hard-working member of society.] Architecture played an important role in achieving that. Modernism was the name of the game and it aimed not only to provide hygiene and harmony, but also to create a new society, here and now.

The dwelling machine, rooted in the utopian, anti-historic Futurism of Marinetti and Sant’Elia, was part of a new world of standardization and prefabrication, but also of speed and urgency. It described living in terms of family size, economic expenditure, functionality, circulations, sun light and health issues. Following his manifesto Vers une Architecture (1923), later revised in La Ville Radieuse (image below, 1935), Le Corbusier took praise of technological advancement and renewal to a utopian degree in his project Plan Voisin (1925), proposing the demolition of a large part of old Paris to erect sixty-story cruciform towers. He considered his partially implemented vision in Unité d’Habitation in Marseille, France, and in the master plan for Chandigargh (India), as proof of the success of Modernism.

Architects soon grew bored with hygiene and technology, however. Constant Nieuwenhuys’ New Babylon (1966) is all about playful man, making full use of his creativity in a totally automated world that does not rely on human labor. People move and inhabit as they see fit a super construction spread around the whole world. Using a similar approach, Archizoom, Superstudio and Peter Cook’s Archigram have provided us with No-Stop City (1969), Continuous Monument (1967) and Plug-in City (1964), respectively, as some of the most enigmatic and radical visions of the future: mega-structures with no buildings, only massive frameworks without boundaries.

All was not bright and happy, however. A mechanized world also generated pessimistic utopias – or rather dystopias, bad places. Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), George Orwell’s 1984 (1949), and Anthony Burgess' A Clockwork Orange (1967) are only few examples. Rem Koolhaas' Exodus (image below, 1972) explores an architecture of rupture and isolation, based on walls and demarcations. He calls the people who would choose to inhabit his fantasy world "voluntary prisoners of architecture."

In the divided Cold War world, each of the competing camps was doing its best to implement its utopian vision of the future not only at home, but in so-called third world countries, as well. The communists sent architectural missionaries to Africa and South Asia to build cities of communal prosperity. The capitalists, on the other hand, praised private property and its finest manifestation: the single family home. Constantinos Doxiadis’ vision for Ecumenopolis (1967) was the stereotypical capitalist city: made of the whole world, where urban areas and megalopolises fused and the world was a single, continuous city spanning the globe.

Utopian ideas, or at least their spatial manifestations, seem to be getting easier to realize nowadays. The development of the Persian Gulf states, American urban sprawl, the European museum cities and China’s urbanization all show that we do not merely want to dream - we want to live in dreams.

The temptation of the unknown, or rather the natural attraction towards change and evolution, has led visionary minds to construct ideal projections of future societies: paradises inhabited by man and governed by the laws of harmony and prosperity. No-where places. And that is what they must remain!

Utopias, and the use of architecture for their implementation, have often been extremely overburdened with expectations about their ability to stimulate social or economic change. Utopias are not meant to be used as blueprints for real-life projects; history has shown that such attempts most often fail. Utopias are much more useful as instruments to reflect on reality, with the hope of stimulating change."

(article originally taken from de+ge website)

(Sofia Architecture Week website)

> Introduction to Richard Neutra and Rush City Reformed

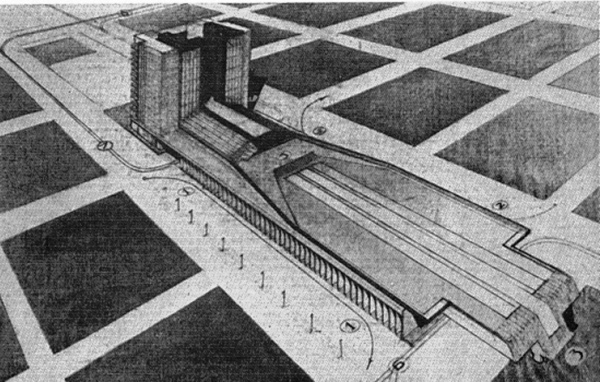

Richard Neutra (1892-1970) is the name of an Usonian architect, born in Austria, who develop a passion for utopian urbanism as other important modernist architects do. His vision about future cities is very similar to Le Corbusier's work, and can be seen in "Rush City Reformed" (1928).

It is a typical modernist utopia: a dispersed city, very organized and perpendicular, monotonous and made for car. These concepts are shocking nowadays, but in the twenties Neutra and his apprentices are naturally excited by mobility technologies, and particularly focused on standard houses that vary depending on family and job types.

It is not so enthusiastic as other urban utopias, but it is interesting to note the accurate forecast about the role of means of transport in our lives. Neutra refused to named train stations, bus stations and airports as "terminals", understanding that we must to learn how to use different means in the same trip. This preoccupation with transport networks results from the mobility disaster inherent to urban sprawl. Neutra wanted accessibility to everywhere, for everyone...

It is not so enthusiastic as other urban utopias, but it is interesting to note the accurate forecast about the role of means of transport in our lives. Neutra refused to named train stations, bus stations and airports as "terminals", understanding that we must to learn how to use different means in the same trip. This preoccupation with transport networks results from the mobility disaster inherent to urban sprawl. Neutra wanted accessibility to everywhere, for everyone...

"In Neutra's "Rush City Reformed" (1928) we see all the familiar marks of the moderns: straight lines, huge concrete slabs holding thousands of resentful working class tenants, and spaces that were as open as they were pointless. But Neutra did Le Corbusier one better by ensuring that no one had any view except that of the flat opposite."

(citation taken form here)

> 'Not Tall Enough' Series - Dubai City Tower

Another Skyscraper in Dubai, another architectural wonder... However Dubai City Tower is just a proposal, for now. It is also known by 'Dubai Vertical City', which means that is intended to include almost everything in 2400 meters (7900 feet) of height - three times the height of Burj Khalifa. In other words, there will be 400 habitable stories and an energy-producing spire on the top.

The idea was exposed in 2008 by Meraas Holding, a Dubai-based real estate investment company who wants to reinforce Jumeirah City. This large neighborhood will be connected to a marina in the Persian gulf, through Dubai City Tower base. Of course this project is very realistic. The Eiffel Tower design starts to be a solution to overcome the wind constraints, and a super-sustainable building using solar, thermal and windy sources, will be a way to get enough energy to maintain this kind of vertical cities. So money is the problem, but this is Dubai...

The idea was exposed in 2008 by Meraas Holding, a Dubai-based real estate investment company who wants to reinforce Jumeirah City. This large neighborhood will be connected to a marina in the Persian gulf, through Dubai City Tower base. Of course this project is very realistic. The Eiffel Tower design starts to be a solution to overcome the wind constraints, and a super-sustainable building using solar, thermal and windy sources, will be a way to get enough energy to maintain this kind of vertical cities. So money is the problem, but this is Dubai...

"The overall mass of the tower that pushes every edge of building design, is broken down into six independent buildings, three rotating clockwise and three counter-clockwise about a central core. The city-in-a-skyscraper will be divided into four 100 story sections linked via a vertical 125 mph bullet train that quickly distributes people between Sky Plazas that separate the different vertical sections.The sheer scale of this project will focus the world’s eye towards Dubai but it will be the tower’s unique design and image that will preserve Vertical City’s grandeur into the future. How high can man go without leaving the earth?"

Structure ID

Name: Dubai City Tower

Place: Dubai, UAE

Height: 2 400 meters

Function: Mixed

Author: Meraas Holding

(citation taken from here)

> Urban Visions in Metropolis

Fritz Lang's masterpiece was produced in 1927, and it is considered the first science-fiction movie, and one of the best dystopian movies of all time. Even with limited visual effects, the silent Metropolis represents very well a creepy vision of the future, which was enough to influence so many artists and to be inscribed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register. Metropolis uses the architecture to express deep social inequalities. These futurist urbanscapes are a result of the Art Deco movement mixed with Lang's first impressions of New York. "The buildings seemed to be a vertical sail, scintillating and very light, a luxurious backdrop, suspended in the dark sky to dazzle, distract and hypnotize." (Lang)

"Metropolis takes place in 2026, where people are divided into two groups: poor workers living beneath the ground and the rich who enjoy a futuristic city of luxury. The tense balance of these two societies is realized through images that are among the most famous of the 20th century, many of which pre-empt such science fiction classics as Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey and Ridley Scott's Blade Runner. Lavish and spectacular, with elaborate sets and jawdropping production values, Metropolis stands today as a testament to Lang's ambitious vision of what cinema could be."

(Metropolis trailer)

.jpg)

.jpg)